“And you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free”

(John 8:32, The Bible)

Millions of people across the world believe the Bible to be the inerrant Word of God. People also trust that the first five books of the Jewish Bible (the Old Testament part of the Christian Scripture), was authored by Moses based on divine revelation. But, many of us now admit that the Bible is very much a human book, and that Moses could not have written the books attributed to him. Scholars had long known this truth. But they mostly kept quiet for fear of retributive action by the institutionalized church that had been routinely burning people, who challenged the legitimacy of its teachings. Fortunately, the situation has since changed. We can now articulate our convictions without risking our lives. Scholarly investigators have now established that the so called “Mosaic Law” was actually assembled by biblical redactors from at least four different sources. These sources have been identified as ‘J’ (Yahwist/Jehovist) , ‘E’ (Elohist), ‘P’ (Priestly} and ‘D’ (Deuteronomist). We also now understand that many of the biblical stories in the “Mosaic” texts are rehashed renderings of ancient pagan myths.

The first chapters of the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, narrate the stories of Creation, Adam and Eve, the Garden of Eden, Cain and Abel, Noah and the story of the Great Flood. Investigators have shown that these Creation stories had been put together from two separate biblical sources, viz. ‘P’ (‘Priestly’) and ‘J’ (‘Yahweh’). Each of these sources presents a differing account of events and a different perspective of the deity driving these events. And many of these stories had originally developed independently of each other from two separate Egyptian mythological traditions. In spite of the outstanding skills of the biblical editors integrating these sources into a single seamless narrative, the tell-tale evidences of the sources and the pagan myths underneath are quite obvious.

Egyptian Mythology

Ancient Egypt had four main cult centres – Heliopolis, Hermopolis, Memphis, and Thebes. Yet, for the most part, Egyptians shared certain common ideas about Creation. For instance, these cults had proposed that in the beginning, there was a universal flood called the Nun or Nu. Through some sort of initiatory act by a single Creator deity, a flaming primeval mountain emerged out of the Nun. And the process of Creation proceeded on this mountain. The chief difference among the various cultic tales of Creation was on the deity responsible for the first acts of Creation and the manner in which the process began. Each cult centre associated its own chief deity with the first acts of Creation.

In Heliopolis, the first deity was Atum, a solar deity. Atum was either the primeval mountain itself or it had appeared on the mountain in the form of a flaming serpent. Atum, apparently a male deity with some female characteristics, gave birth to a son and a daughter – Shu and Tefnut, representing air and moisture. Shu and Tefnut produced their own son and daughter – Geb and Nut – identified with Earth and Heaven. These four children (Air, Moisture, Earth and Heaven) corresponded to the basic elements of the universe. Geb and Nut (Earth and Heaven) in their turn produced four more children – Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. Thus, in the beginning, nine deities – Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys – collectively known as Ennead (i.e. the group of nine), came into existence.

The city of Memphis had served as the first capital of Egypt for almost a thousand years (c. 3100 BCE – 2100 BCE). The chief deity of Memphis was Ptah, a crafts god. The Memphites claimed that it was Ptah, through the spoken word, who had summoned forth Atum from the universal flood (Nun). In all other respects, the Memphis cult had generally adopted the Heliopolitan traditions.

The cult in the ancient city of Hermopolis had believed that in the beginning, eight gods – four male and four female – had emerged out of Nun. These eight gods collectively gave birth to the solar deity Re, who initially appeared as a child floating on a lotus. In one of those strange concepts of mythic tradition, Re was both the child and creator of these first eight Hermopolitan gods collectively termed the Ogdoad (i.e. the group of eight). In the Hermopolitan tradition, these four male-female pairs represented the four basic elements of the primeval universe.

Thebes that had come to power at about 2040 BCE was a late arrival on the political scene. The deity of the Theban cult was Amen. The Theban priests claimed that the Creator deities of the other cults were just another form of Amen. Thus, according to the Theban theology, Amen first appeared in the form of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad, then appeared in the form of the Memphite Ptah, then in the form of Heliopolitan Atum, and then in the form of Hermopolitan Re, who by this time had become the most important solar deity in Egypt. This succession of forms of the deity necessitated some variations from the Creation myths associated with these deities in their own cults. But such a fit enabled Thebes to promote their own go Amen as the chief deity, without alienating the other cults.

The Egyptian mythology had evolved through the study of their natural surroundings. They had observed two major factors that controlled their ancient world – the annual flooding of the Nile that fertilized the land and the daily and annual movements of the sun. The annual correspondence between the Nile flood and the solar year linked the two events in a harmonious relationship. Both cycles suggested birth, resurrection, and everlastingness. Thus, the many deities associated with different aspects of Creation in the different cult centres of Egypt, came to symbolize the features of the natural order.

Mythology in the Bible

It is likely that the Israelites had acquired an understanding on these Egyptian myths and traditions, while they had lived in Egypt. These myths had become current, influential, and well-known throughout Canaan (Palestine) after Israel had settled there. In the end, the Hebrew theologists fashioned a new cosmology rooted in ancient Egyptian and other polytheistic mythologies by reworking those stories to reflect their own monotheistic viewpoint. In other words, there is nothing original or divine about the Creation accounts in the Bible. And it is not very difficult to establish this reality.

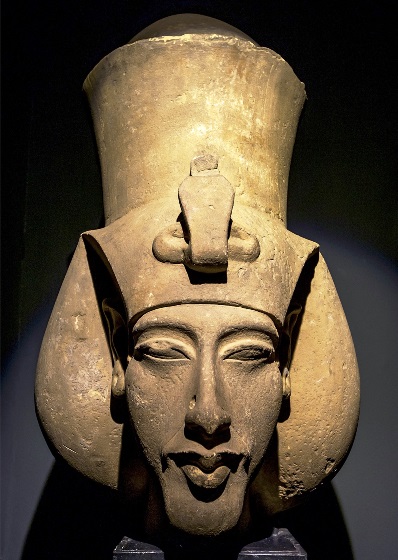

As already mentioned, the biblical Creation account comes from two sources – ‘J’ (Jehovist) and ‘P’ (Priestly). The roots of source ‘J’ apparently go back to the teachings of Egypt’s most influential religious centres – the city of Heliopolis (biblical ‘On’). The Bible reveals a close relationship between Heliopolis and Israel. For instance, Joseph, one of the sons of the Jewish patriarch Jacob (whom God had renamed ‘Israel’), was heir to the covenant between God and Israel. The biblical story says that Joseph had become the friend and the deputy of the Egyptian Pharaoh. Also, Joseph had married Asenath, “the daughter of Potiphera, priest from the city of On” (Genesis 41:45). Joseph’s half-Egyptian son Ephraim, whom his grandfather Jacob had appointed to be Joseph’s heir, was educated in the Heliopolitan traditions. Incidentally, Heliopolis had turned the centre of a monotheistic religious cult (Atenism) under the Pharaoh Akhenaten that challenged traditional Egyptian polytheistic religious beliefs, at a time not much before the Exodus of the Israelites to Palestine.

On the other hand, source ‘P’ had adopted the creation legend associated with the Egyptian city of Thebes. Thebes was the political and religious capital of Egypt during the time Israel had lived in Egypt. The Theban viewpoint itself was an attempt to integrate conflicting Egyptian traditions from other major Egyptian cult centres, including that of Heliopolis, with its own local religious beliefs.

The Hebrew theologians looked at the Egyptian deities and identified the aspect of nature represented by a particular god or goddess. The early Hebrew scribes separated the deity from the phenomena represented by the deity. They then described the natural events, without clubbing the deity with it, but in the same sequence in which these deities appeared. For instance, the Egyptians had Atum appear as a flaming serpent on a mountain that had emerged out of the universal flood (Nun); but the Hebrews adapted the myth by dropping off the deity and picking out only the light appearing while a firmament arose out of the primeval waters. However, with different Hebrew writers emphasizing different Egyptian traditions, conflicting histories of Creation developed.

The Babylonian Connection

The Egyptian connection to the Jewish Scripture is only just part of the story. The Israelite writers living in Palestine had also been periodically exposed to the influence of other great cultures of the ancient Near East. And in 587 BCE, the remnants of the Hebrew kingdom were captured by the Babyl18onians and forcibly removed to the homeland of their captors. This Babylonian Exile immersed the Jews in the local culture. Eventually, Babylonian wisdom influenced the Jews to further refine their earlier ideas adapted from Egyptian mythology.

The biblical story of the Great Flood reflects this later Babylonian influence. The original biblical Flood story was apparently based on Hermopolitan traditions about the Ogdoad – eight gods comprising of four males and four females emerging out of the primeval ocean. There was no Adam and Eve or the Garden of Eden in this Creation account. But, the Jews in Babylonian Exile encountered a new worldwide flood myth. The source of this flood story was from what was perhaps the oldest written tale on the planet – the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh dating back to nearly 5,000 years. The great sage Utnapishtim was warned of an imminent flood. He builds a huge boat, reinforced with tar and pitch, which carries his relatives, grains and animals.

The Hebrews now decided to synchronize their own history with that of the learned Babylonians. They moved the flood story from the beginning of Creation to the tenth generation of biblical humanity. Consequently, the Flood story became part of the story of Noah, the tenth generation biblical patriarch. The eight gods, comprising of four males and four females, emerging out of the primeval waters in the Egyptian Creation myth, apparently, became Noah, his wife, his three sons and their wives – the eight people who had survived the Great Flood, in the Noah story.

In spite of the painstaking efforts of the Jewish scribes to weave a seamless tapestry of monotheistic history, traces of the original polytheism remain embedded in their texts. Also, since the stories were compiled based on multiple sources, many contradictions have been preserved. As the Hebrews lost contact with their Egyptian roots, they could no longer explain away some of the contradictory material in the earlier sources. And, over time, oral traditions supplemented the written texts. These influenced later beliefs and editing practices, resulting in more distortions. Today, it is not very difficult to identify the initial Egyptian myths that underlie the biblical stories and show how, from time to time, Babylonian myths were grafted on to earlier texts or how portions of the original stories were substituted.

The Two Stories of Creation

The Book of Genesis begins with two separate and contradictory stories about Creation. The first story, attributed to the Priestly (P) source is found in Genesis 1–2:3. It presents the familiar account of the seven-day creation proceeding in a structured sequence of events starting with the formation of heaven and earth and moving through the manifestation of vegetation, animal life and, finally, humans. This story does not mention Adam and Eve as people assume. This first story only refers to the creation of a collective entity, male and female, in God’s image. The second account of Creation, attributed to the Yahwist (‘J’) source, is in Genesis 2, starting from Genesis 2:4, which is not as complete as the priestly version. This account serves as an introduction to the story of Adam and Eve and their children.

These two Creation stories in the Bible differ in many details. Each provides a different order of Creation and different explanations on how things came about. The first Creation account says nothing about moral principles. The second story deals primarily with issues of moral concern – sin, murder and punishment. It also introduces something named the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Some of the central moral principles of Western Civilization, such as original sin, moral accountability for one’s actions etc. arise out of this second story. Also, each story presents its own name and image of the deity: The Priestly (P) source (like the ‘E’ source) names the deity as Elohim (God). It portrays an all-powerful disembodied spirit that can summon forth elements of the universe with a word, wink, or snap of the fingers… In contrast, the deity of the ‘J’ story Yahweh (Jehovah) is anthropomorphic (humanlike), who likes to putter around in the Garden of Eden and sculpt little figurines…

Since average theologians are more concerned with the need for biblical inerrancy, they mostly ignore the differences and treat the two stories as part of the same cycle – the first story presenting the cosmic picture and the second one presenting the human dimension. On the other hand, scholars, willing to acknowledge contradictions admit that there are two stories that have different origins and that subsequent editors had attempted to integrate the two into a single narrative, but had left several telling signs of the true sources. Irrespective of what the church teaches or the faithful believes, the truth remains that the P and J sources had its origin in separate Egyptian traditions.

The ‘P’ story flows from images in the Theban Creation myth. It unfolds with the same sequence of events. The description of the primeval world before the act of Creation corresponds precisely with the characteristics of the Ogdoad, the first form of Amen in the Theban myth. The story proceeds with the spoken word of Ptah and the first light of Atum. A mountain emerges out of the primeval flood, heaven and earth are separated, the waters of the Nile are gathered together and vegetation appears. The process concludes on the sixth day with the creation of an entity (labelled in Genesis 5 as “the Adam,”) in the image of God. On the seventh day, God rested.

A close examination of the details suggests that the redactors of the text had left some “cut and paste” errors in transcribing the P text. It looks like the first humans (“the Adam”) was actually created on the seventh day and God rested on the eighth day – assuming that God would get tired and require a day’s rest! (We cannot go into the details about how God rested on the eighth day rather than the seventh day here, owing to constraints of space. Maybe, the matter could be considered in a follow up article.)

Unlike the ‘P’ story, the J story retained only its core Egyptian identity. It later became layered with several elements from the corpus of Babylonian literature. Initially, events in the Garden of Eden were about the children of Geb and Nut and the conflicts among them. The Garden of Eden lay along the Nile. The ‘Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil’ and the ‘Tree of Life’ were derived from symbols associated with the Egyptian deities Shu and Tefnut. The sons of Adam and Eve – Cain, Abel, and Seth – corresponded to the sons of Geb and Nut – Osiris, Set, and Horus. The feuds between the family of Adam and the serpent, and the feud between Cain and Abel were based on the feuds between the family of Osiris and the wily serpentine Set. Unlike, the simple and precise story with virtually no characters other than God in the P account of Creation, the J story is crowded with characters. Consequently, J acquired a number of accretions, especially from Babylonian sources. . Of course, it is hard to recognize the earlier Egyptian roots without the benefit of the larger context into which the stories have been placed.

The Two Flood Stories

While it is easy to distinguish between the two versions of the Creation stories since they appear one after the other in the Bible, the two flood stories are tightly woven together and hence difficult to separate. A sentence sometimes begins with one version and finishes with the other. Both the J and P flood stories were originally based on the Hermopolitan Creation myth. After they were integrated, the text was further modified to reflect Babylonian traditions about a flood.

But, the flood story still reveals its two sources. For instance, one story says that a pair of each animal was taken into the Ark. But, the other story says, when it came to ‘clean’ animals, seven pairs were admitted into the Ark. Now, think of the calamity if there was only one pair of each kind of animal in the Ark. The world would have lost for ever, many animal species, after Noah had sacrificed some of the ‘clean’ animals immediately after the flood, in order to keep the deity in good humour!

—————————