“Thou art in my heart;

There is no other that knoweth Thee,

Save Thy Son, Akhnaton.

Thou hast made him wise in Thy designs

And in Thy might.”

(Akhenaton—Longer Hymn to the Sun – Translation by J H Breasted)

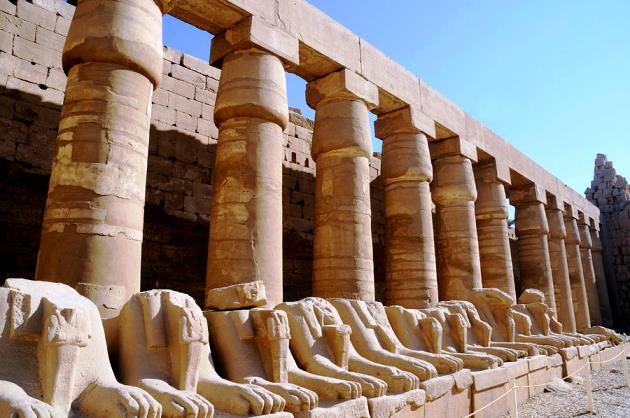

Karnak Temple, Egypt (Ancient Temple of Amen in Thebes)

Most people tend to believe that monotheism came into the world through Judaism. The Hebrew Bible says that Moses had laid the foundations of the faith. But the history of ancient Egypt reveals that one of her monarchs was an earlier apostle of monotheism. Moses came from Egypt and it is quite likely that he brought the idea from Egypt to Israel. The adherents of monotheism would be dismissive of such a suggestion. They are told that their faith was sent down from the sky. But archaeologists have dug up enough evidence in the last century to establish the fact that Pharaoh Amenhotep IV had tried to implement monotheism in Egypt. Of course, his mission ended in disaster.

This article is the first part of a multipart summary of the story of the monarch, who was too saintly to succeed in his religious zeal:

Some fourteen hundred years before Christ, when Egypt was at the height of her power, Pharaoh Amenhotep III died after a long life of worldly luxury and display. No nation ever stood in direr need of a strong and practical ruler than did Egypt at that moment. Yet, at this fatal juncture, this mighty empire chanced to be ruled by a young dreamer. His name was Amenhotep IV. He was less than fifteen years of age, when he succeeded his father to the throne. And his reign lasted just around fifteen years. He was less than thirty years old at his death.

Amenhotep IV was born as the heir of an empire that had stretched from the Sudan to the borders of Armenia, and of a culture more than four thousand years old. He was the last offspring, in direct descent, of a long and glorious line of warriors overloaded with the spoils of conquest. His ancestors had freed Egypt from foreign domination. His great-great-grandfather had made the nation the head of an empire. His father, Pharaoh Amenhotep the Third, whom some modern writers rightly called ‘Amenhotep the Magnificent’, had lived a life of pleasure, with a number of beautiful wives and concubines collected from every country of the known world. But his only son and successor turned out to be meek as a lamb!

Amenhotep IV was the tenth Pharaoh of that glorious Eighteenth Dynasty, which opens the period known in history as the “New Kingdom.” His father had utterly crushed the sporadic revolts in Nubia (southern Egypt and northern Sudan) and in Syria, bringing peace to the land after the unceasing struggles of the former reigns. Tribute in gold and silver, in ivory and slaves, and cedar wood poured in regularly from all parts of the immense empire. The granaries were full and the people content. Thousands of foreign slaves were toiling for the welfare of Egypt. And the faraway kings of Babylon and of Mitanni – the brothers-in-law of the Pharaoh – and the king of the Hittites and the king of barbaric Assyria wrote in their dispatches to Amenhotep the Third: “Verily, in thy land, gold is as common as dust.”

The name ‘Amenhotep’ meant, “Amon is pleased,” or “Amon is at rest”. Amon (Amen/Amun) was the god of Thebes, the capital city of Egypt. The Pharaohs had ruled from Thebes for long. They were believed to be the sons of Amon and hence divine. But the new ruler had styled himself as the Son of that unseen, everlasting source of all life – the Energy of the Sun. Through the visible disk of the Sun, he had been worshiping “the Energy within the Disk”. ‘Aton’ was the name of this deity. He declared that there was only one true god and it was ‘Aton’.

Thebes was not merely one of the largest and most sumptuous cities of the world; it was the masterpiece in which the genius of the ‘Near and Middle East’ had expressed itself. Nothing equalled the beauty of its monuments, the pomp of its festivities, and the wealth of its priests. The temples of Thebes stood in all their glory. Their dusky halls inspired sacred awe; their rows of mighty pillars displayed harmony of proportions and grace blended with majesty. (The gigantic ruins of ancient Thebes still stir the admiration of travellers.) Thus, in wealth, in splendour and in warrior-like fame, stood Thebes, the seat of divine royalty and the proud City of Amon, the mighty god of the illustrious Pharaohs. The skills of all known lands had adorned it; the sword of its kings had spread the glory of its name far and wide. (Karnak is the modern-day name for the ancient site of the Temple of Amon at Thebes.)

The Charuk palace, the residence of the Pharaoh Amenhotep the Third, was built on the western bank of the Nile. It was a beautiful structure of brick and precious wood, decorated with exquisite paintings and surrounded by immense gardens full of shade and serenity. From the terraces of the palace one beheld to the east, beyond the Nile and its palm-groves, Thebes in all its glitter and glory. In the foreground, the towering pylons of the great temple of Amon emerged above the outer walls of the sacred enclosure that stretched over miles. And the gilded tops of innumerable obelisks glittered in the dazzling light or glowed in the purple of the sunset. To the west was the vastness of the desert…

Amenhotep the Fourth was born in the Charuk palace in about 1395 BCE. His mother, Queen Tiy, was the chief wife of Amenhotep the Third. After his long life of pleasure, her weary lord had gradually brushed aside the tiresome duties of kingship. So, it was Queen Tiy who had dealt with much of the affairs of the state. She received the foreign ambassadors, gave orders to provincial governors and drafted the dispatches to Babylon or to the faraway capital of the Hittites. And she saw to it that the public officers did their work well and that the taxes came in promptly.

The Queen’s favourite deity was the god of the sacred city of Anu or On (“the City of the Obelisk”). The Greeks would one day call this city Heliopolis (“the City of the Sun”). The god of On was the oldest Sun-god Ra (Re), also known as Aton, represented by the Sun-Disk. Although the queen was a devotee of god Aton, the name of Aton was still that of a secondary god among many. Among the gods, Amon, the god of the capital city of Thebes, was the most popular, The priests of Amon used pious devices to impress the people, and even force their will upon the kings. Maybe, the queen had wished that one day, god Aton would, become the supreme god of the realm and the god Amon and his priesthood would lose its clout.

Queen Tiy was fairly past thirty-five, when she bore the little prince, her only son. Few children ever were so desperately looked forward to and so much loved as the only son of Amenhotep the Third and Queen Tiy. The whole nation erupted in joy and celebration at the birth of the heir to the throne. Sacrifices of thanksgiving were offered to the gods. Vassals far and near welcomed the infant who would be their lord one day. The life of this prince would last less than three decades.

In all likelihood, the Sun-worshipper mother had taught the child to render homage to the Sun. His later passionate adoration of the Sun could be traced to the impressions of his childhood. But, the queen was no monotheist. So, the religious ideas her son later developed were decidedly his own. As he grew in years, he became more and more devoted to the life-giving Disk – the one God he loved with all his heart and all his soul. One of his hymns says, “Thou art in my heart, and no one knoweth Thee save I, Thy Son.” (The amazing words of this saint-king come down to us, recorded upon the walls of a tomb, after he has lain in total oblivion for some thirty-three hundred years.)

Amenhotep IV was married, sometime before his father’s death, to a princess called Nefertiti. It is not certain whether she was an Egyptian or a foreigner. In about 1383 BCE, the young prince ascended the throne of his ancestors as Amenhotep the Fourth, king of Egypt, emperor of all the lands extending from the borders of the Upper Euphrates down to the Fourth Cataract of the Nile. His accession was greeted widely.

The young Pharaoh spent much time thinking of his sole God Aton – the energy of the Sun. To him, the Sun was the supreme source and embodiment of all that appeared to him worth adoring: beauty, power, heavenly majesty and kindness. He had conceived a more subtle idea of Godhead by considering the “Heat” or “Heat-and-Light”-(Shu) – which-is-in-the-Disk. It is the god Ra-Horakhti of the Two Horizons. And one of the long succession of his titles as the Pharaoh was “High-priest of Ra-Horakhti of the Two Horizons.

The Pharaoh’s first important act (of which there is any record) was the erection of a temple to his sole god Aton in his capital Thebes. Like all the buildings consecrated to the Disk, that temple was utterly destroyed in subsequent years by the enemies of the king’s faith. Nothing is left of it save a few blocks of sandstone, detached from one another, which were mostly re-used in the construction of later monuments. There was a figure of the king praying to Amon while the Sun-disk with rays ending in hands shed its life-giving beams upon him. Although, this image was effaced later, traces of it are still visible.

The king’s next step was to decree that the quarter of Thebes in which the newly-built temple to Aton stood would henceforth be called “Brightness of Aton, the Great One”. The Pharaoh also renamed Thebes —the proud City of Amon, whose patron-deity had become the god of a whole empire— as the “City-of-the-Brightness-of-Aton.” At that stage he had not suppressed the cult of Amon or of any other gods elsewhere. Probably, at this stage of his career, the Pharaoh had no plans of banning other deities. Nevertheless, by changing the name to the capital of his fathers, he was paying public homage to the one true God of the whole universe, as opposed to all the man-made traditional gods. Incidentally, he had forbidden the making of images of Aton, on the lofty ground that the true god has no form. (This idea of monotheism and the prohibition of making the images of the deity were apparently borrowed later by Judaism).

The priesthood of Amon was a rich and powerful body. In their eyes, Amon was the actual sovereign of the land. It was this god who had caused his sons, the Theban Pharaohs, to be invincible in war and magnificent in peace. And it was the established custom that the Pharaohs should visit the shrine of their benefactor god Amon every day to perform certain traditional rites and receive from Amon a daily renewed supply of divine power, in order to sustain their age-old claim to divinity.

His father had evidently made some attempt to shake off the priestly hand that lay so heavily on the sceptre. For instance, traditionally, one of the High Priests of Amon was chief treasurer of the kingdom, and another was the grand vizier of the realm. Amenhotep III had appointed a vizier, who was not the High Priest of Amon. The fact that such extensive political power was being wielded by the priesthood of Amon must have intensified the young king’s desire to be freed from the sacerdotal thrall that he had inherited. But he failed to gauge the dangers of interfering in the affairs of the priesthood of Amon. Even monarchs cannot touch the traditions of faith without burning their fingers!

We do not know at what stage the young Pharaoh ceased to conform himself to the practice of paying daily homage to god Amon. Perhaps, he gave up the paractice very early in his reign. No doubt the priests strongly resented this break with the traditions. What they resented more was the steady decrease in the revenues of their temples, now that the king had withdrawn from them the habitual royal gifts that were enormous. As long as the Pharaoh had contented himself with honouring his god without banning other deities, the priests of Amon kept their peace.

But when the Pharaoh altered the name of the capital, he was making public his intention to place his own conception of Godhead above the established gods of the realm. That stirred the fury of the priesthood. But the king was not shaken. He was a pacifist; he did not use violence against anyone. But he issued a series of new decrees of an uncompromising spirit, by which all hopes of future reconciliation were annihilated.

The priests of Amon were dispossessed of their fabulous wealth; the name of Amon and the plural word “gods” were erased from every stone. Even the compound proper names which contained the name of the Theban god were not allowed to remain. The young Pharaoh was so enthusiastic in his mission that he did not hesitate to erase even the name of his own father from the inscriptions in his tomb. And the Pharaoh changed his own name from Amenhotep to Akhenaton—“Joy of the Disk”/“Joy of the Sun”. (It is also spelled Akhenaton/Akhenaten/Ikhanaton etc.) The Pharaoh abolished the cult of Amon and also the cults of innumerable other national gods and goddesses. All the images of gods were destroyed. (Exactly what the Jews did while occupying their Promised Land!)

When Akhenaton had the name of god Amen hacked out from his father’s name, his people saw it as a blasphemous impiety. Dishonouring the ancestral dead was totally unacceptable to them. And behind the scenes, the priests plotted against the ruler. The considered him a heretic. In the seclusion of their homes, the populace continued to worship their ancient and innumerable gods. The crafts that had depended upon the temples and traditions muttered their anger in secret against the king. Even his ministers and generals of the Pharaoh started hating him. In private, most people cursed their king and prayed for his quick death. But the Pharaoh was unwilling to stop.

Pharaoh Amenhotep IV had unprecedented greatness in the world of ideas. But he was not fitted to cope with a situation that demanded an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader. He failed miserably to understand the practical needs of his empire. His focus was more on implementing the monotheistic faith of his god Aton. Such a transition from age old polytheistic superstitions deeply rooted in the needs and habits of the people should have been carried out slowly by softening it with intermediate steps. But the young Pharaoh was a poet. And he was in a tearing hurry. At one blow, he forbade the worship of deities made dear by long tradition and belief. He dispossessed and alienated a wealthy and powerful priesthood. And that was the right recipe for disaster!

The trouble stirred up by the servants of Amon after the renaming of Thebes taught him that the national gods were indeed “jealous gods,” in the sense that, as long as their priests remained in power, no truer and broader conception of the divine would find its way to the hearts of the worshipers. The priesthood would keep the people bound to a state of satisfied religious routine. They will keep people enslaved under the weight of a vain formalism. That is what profited the priesthood. The Pharaoh realized that if he allowed the priests to hold their sway, his god would never receive the whole-hearted acceptance of the public. He saw that the rivalry was between national tradition and universal truth. One of the two had to go.

Akhenaton realized that the city of Thebes that clung to its patron god Amon was not the place where the first seeds of truth could be sown. Perhaps, somewhere down the Nile, in an out-of-the-way spot a new city could be founded— the capital of a new State, which could one day become the model of a new world. He would build that ideal State with the help of the few who, if they did not always understand him to perfection, at least seemed to love him. The cult of the one impersonal God would prevail there. The standards of the enlightened few would be the official standards. And the name of Amon and all it stood for would be unknown in that new city!

In the sixth year of his reign, when he was about seventeen or eighteen, Pharaoh Akhenaton sailed down the Nile in search of a suitable location to build a new capital for the Empire – the paradise of his dreams.

(To continue…)

Select References:

- Sigmund, Freud Moses and Monotheism

- Savitri Devi, Son of the Sun

- Ahmed Osman, Moses and Akhenaten: The Secret History of Egypt at the Time of Exodus

- James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest

- James K. Hoffmeier, Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism

- Jan Assmann, From Akhenaten to Moses Ancient Egypt and Religious Change