“.. should not a people seek their God? Should they seek the dead on behalf of the living? “

(Isaiah 8:19, NKJV)

On October 13, 2019, Pope Francis declared five dead people Saints – four of them women. One of the women elevated to sainthood is a Catholic nun from Kerala. The Pope said, “today we give thanks to the Lord for our new Saints. They walked by faith and now we invoke their intercession.” I am not sure whether the making of saints or invoking their intercession has any scriptural authority. Of course, the scripture can be interpreted in quite convenient ways. Nevertheless, one cannot miss the reality that much of the religious system and practices in the churches, particularly in the Roman Catholic Church, are actually rooted in Roman paganism. And saint-making too has a pagan background.

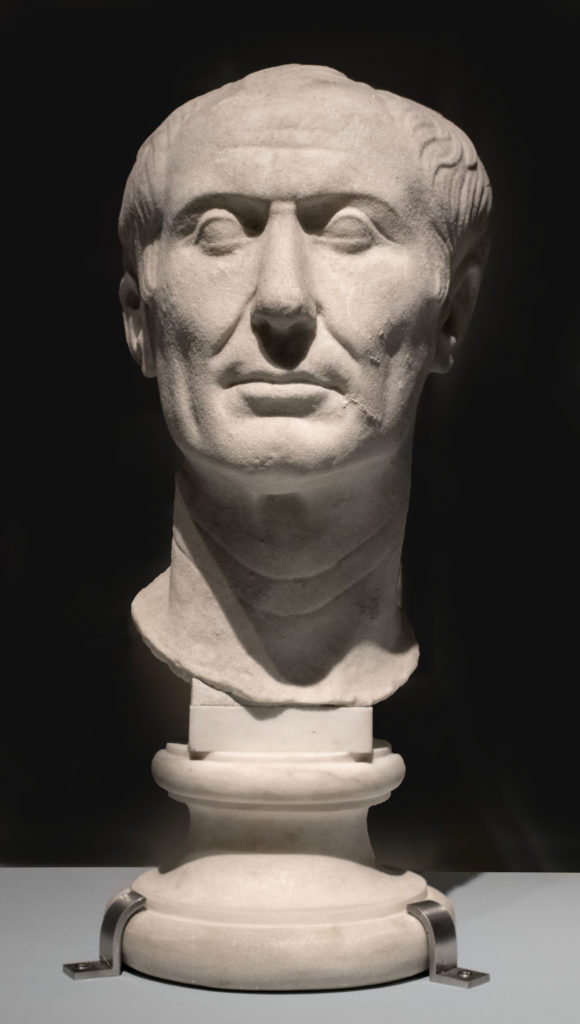

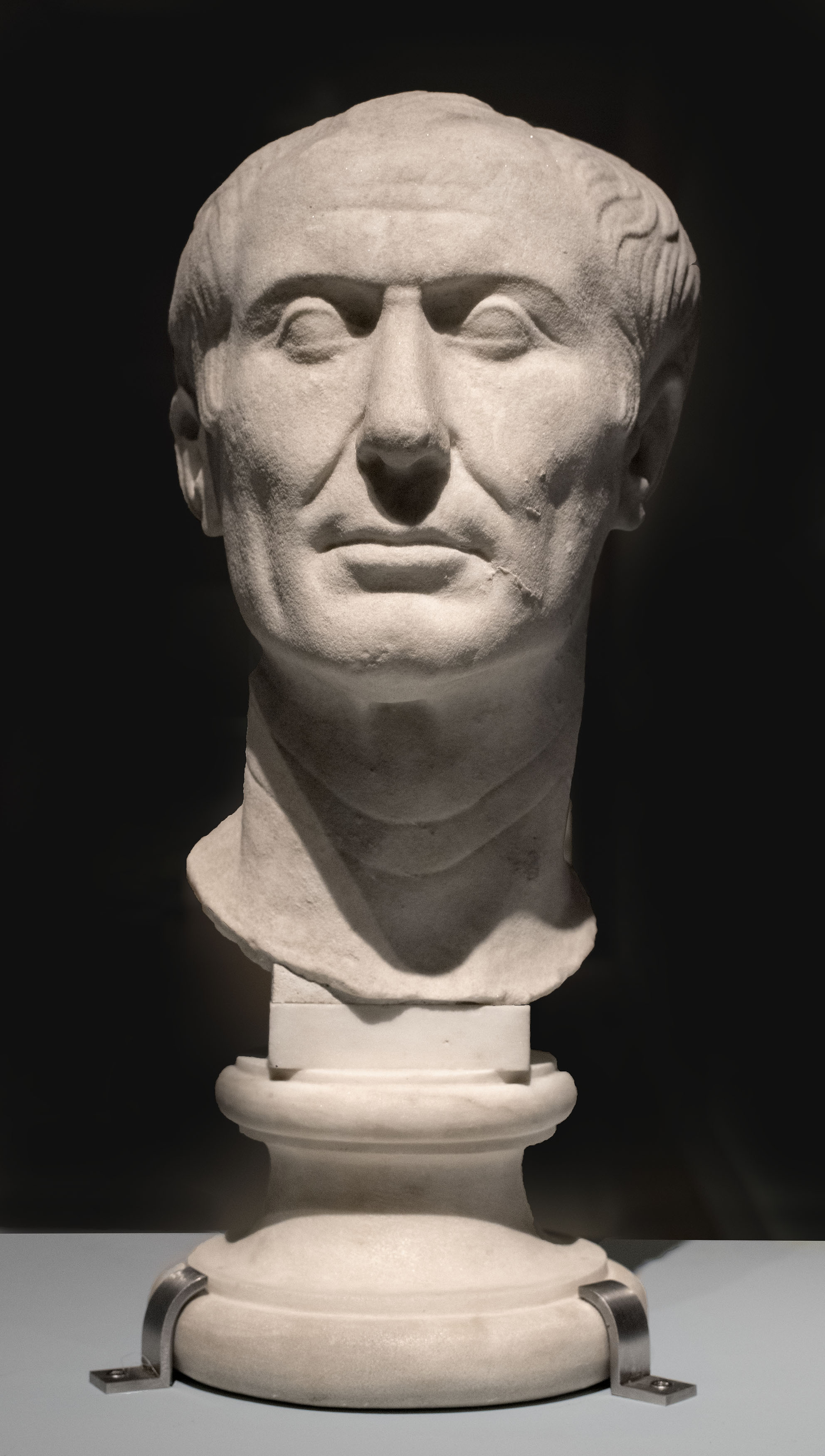

Julius Caesar, the Roman ruler was assassinated in 44 BCE . In 27 BCE his nephew Octavian became Roman Emperor with the name Augustus Caesar. He converted Rome from Republican to Imperial system. Thus, Augustus was the first Roman Emperor and remained in office until CE 14. (According to the New Testament, Jesus was born during the reign of Augustus Caesar).

In the household, the head of the family performed religious rituals. Beyond the home, gods were worshipped by the state, which employed colleges of highly trained priests. The most important body of priests was the Collegium Pontificum (“College of Pontiffs”), whose members were the highest-ranking priests of the state religion. This council of priests consisted of the Pontifex Maximus (Chief Priest or High Priest) and the other pontifices. In 12 CE, Emperor Augustus declared himself the Pontifex Maximus. Thereafter the post of Pontifex Maximus vested with the Emperors.

Turning political leaders into gods was an old tradition around the Mediterranean. Aeneas and Romulus, the legendary founders of Rome, were already worshipped as gods. So, when the Halley’s Comet passed over Rome early in his reign, Augustus announced that it was the spirit of Julius Caesar entering heaven. Only the spirit of gods entered heaven. If Caesar was a god then, as his heir, Augustus was the son of a god entitled to be worshipped by his subjects.

The fundamental source of emperor-worship is to be found in one of the primitive tendencies of Roman thought, viz., the veneration of the individual human spirit, the worship of the Genius. The households worshipped the Genius of the father figure in the family. So the Romans conceived the Emperor as the father of the nation. The constantly recurring worship of the Genius of the father by the whole household could not fail to suggest the worship of the Genius of the emperor on the part of all his subjects.

Also, primitive Roman was a strong believer in the divinity of the souls of men after death. The sentiment was naturally most strongly felt by each person toward the spirit of his own ancestors. Since the spirits of ancestors were believed to influence the lives of their descendants for good or ill, offerings were made to them to secure their favour and fixed days for such offerings were appointed in the Roman official calendar. Thus, the worship of the Genius facilitated the introduction of the cult of the living emperor. And ancestor-worship in like manner prepared the way for the deification of the emperors after death. The Roman worship of rulers began with Julius Caesar. The senate formally conferred upon Caesar the title of Divus, “the deified,” and ordered a temple to be erected for his worship.

As the grand-nephew and adoptive son of Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar used the title Divi Filius in documents and on coins. The title Augustus, “the venerable,” conferred by the senate and adopted by him as a surname, had a religious significance and marked him as more than man. After his death in 14 CE the senate passed decrees conferring upon Augustus the title Divus and providing for his worship as a god. (Source: The Worship of the Roman Emperors, Henry Fairfield Burton (The Biblical World, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Aug., 1912))

Tiberius succeeded Augustus and reigned from 14 CE to 37 CE. (The crucifixion of Jesus and the commencement of the Jesus Movement occurred during the reign of Tiberius.) Although, the unpopularity of emperors like Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, and Domitian prevented their deification by the Senate, they had been worshiped in their lifetime, especially in the eastern provinces. (Christians who refused to worship the Roman gods and the Emperor were persecuted and many were martyred). Other members of the imperial family besides reigning emperors frequently received formal deification. The total number of persons who were raised to the rank of Divi during the five centuries from Julius Caesar (In office from 49 BCE to 44 BCE) to Valentinian III (Emperor from 425 to 455) was seventy-four, of whom thirty-eight were rulers of the whole or a part of the empire, and sixteen were women.

This Roman practice of deifying living and dead rulers appeared quite attractive to the church leadership. It apparently thought that if a temporal ruler or the Roman Senate could confer the status of god upon people, there was no reason why the true representatives of Jesus Christ reigning over the ecclesiastic realm should not make its own gods! However, the use of the term ‘god’ or ‘deity’ sounded a bit unfit for church use. So they decided on the term ‘Saint’. Both were people who supposedly received direct admission into heaven after their demise.

Thus the Roman Catholic Church elevated all of its first thirty-five bishops (Popes) to sainthood with retrospective effect. Seventeen out of the subsequent 19 Popes too were made saints. Once Constantine I, a Christian sympathiser, became the Roman Emperor the door to martyrdom came to be blocked up. So, the church found it difficult to canonize many of its later Popes. But, there were other people who could qualify to be saints. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, there are more than 10,000 saints recognized by the Roman Catholic Church, though the names and histories of some of these holy men and women have been lost to history.

When the Church became a dominant political force after Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire, each local Christian community felt the need of having their own saints and martyrs. So they started to resort to anything that could be adapted to pre-existing templates about stories of martyrdom, in order to fill their chapels and festivities with appropriate figures to be revered. This is not to suggest that there were no genuine martyrs and saints. However, in all likelihood, the miraculous parts of their official stories are mostly nothing but a dramatic fabrication. But it filled the cash chests of the churches concerned, since people were ready to throw money at anything in the name of miraculous boons. (Currently the power to make saints in the Roman Catholic Church is vested solely with the Vatican).

These inventions of grounds for sainthood often have a farcical quality, in which independent narrative elements mix in unpredictable and spectacular ways. For instance, there is this story of St Veronique, in which a female character by the name of Bernice (a classical Greek name, meaning ‘bearer of victory’: bere nike) mentioned in passing in an apocryphal Passion gospel of the 4th or 5th century, is transformed by way of a false etymology in Veron Icon (‘the true image’). She has been presented the bearer of the linen with which Jesus supposedly cleaned his face while he was taken to the cross, miraculously leaving his image on it… a cloth of which numerous churches claimed to possess the ‘true’ one during and after the Middle Ages. (There are many such tricks to covert ordinary shrines to pilgrim centres).

Other cases consist in the transmutation of some pagan cult. For instance, the Christians transformed the Celtic goddess Brigid into St Brigid, one of the patron saints of Ireland, to which the traditional festivities, places of cult, and legends of the ancient goddess were simply transferred. Less amusing are cases like that of St Catherina of Alexandria, who seems to be the mere reversal of the historical figure of the pagan scientist-philosopher Hypatia, actually killed by Christian mobs. She was turned into a legendary studious girl supposedly assassinated by pagan hordes.

But the funniest story of all is that of the saints Barlaam and Josaphat. These two characters appeared in a religious romance probably composed in Syria around the 7th or 8th century, and that quickly became popular in the territory of the Byzantine empire, and later in Western Europe, where it was re-elaborated and copied again and again, even as late as in the 17th century, when the two legendary monks became the protagonists of a playwright by the prominent Spanish writer Lope de Vega.

Candida Moss says in her book ‘The Myth of Persecution’, “Josaphat was an Indian prince, who was converted to Christianity by the hermit Barlaam [that supposedly had been himself a disciple of the apostle St Thomas]. Astrologers had predicted at his birth that he would rule over a great kingdom (…), a prediction that led his father to shut the boy away in seclusion. Despite his father’s best efforts to keep him from the world, Josaphat realized the horror of the human predicament through encounters with a leper, a blind man, and a dying man. His view of the world thrown into jeopardy, he then met Barlaam the hermit, converted, and spent the remainder of his life in quiet contemplation of the divine. If this story sounds familiar, it should. It is nothing but a Christianized version of the life of Siddhartha Gautama, the Indian prince who became the Buddha (…) It isn’t just the broad plot details that are similar; minute plot details and even phraseology are identical. Even the name Josaphat is just a corruption of the word Bodisat or Bodhisattva, a title for the Buddha meaning an enlightened person.”

In this case, the ‘fabrication’ of Josaphat (or Joasaph, in other manuscripts) was not deliberate, but the accidental result of human error. The story just grew and spread, moving from one region to another, translated and re-translated into different languages and in countries with different cultures and religions, until a Christian monk took it for a real history about real Christian people. Barlaam and Josaphat were canonized both in the Orthodox and in the Catholic churches, celebrating their festivity in the West on November 27 until after the historical mistake was discovered and rectified not many decades ago.

The online Catholic Encyclopedia says (about St Josaphat): “The story is a Christianised version of one of the legends of Buddha, as even the name Josaphat would seem to show. This is said to be a corruption of the original Joasaph, which is again corrupted from the middle Persian Budasif (Budasif = Bodhisattva).”

At the practical plane, there are hardly any differences between the worship of Roman deities and the saints of the church. The Roman deities were represented in effigies. The Christian saints too are so represented although Christians are strictly prohibited from worshipping images. There was always an altar before the Roman deities so that people could offer their sacrifices. The church replaced it with a platform on which the worshippers could place candles or other gifts. An additional item in the church is a collection box into which the devotees could put currency notes and coins. (Unlike in the pagan Roman Empire, the saints of the church are big money spinners – the primary incentive for saint-making!) In the ancient Rome, the arrangement was purely that of quid pro quo – I scratch your back and you scratch my back. I will offer you a sacrifice or a feast. (The saints have feast days even in Christianity). You reciprocate it with a safe delivery for my cattle and my daughter-in-law. And make sure that my cattle deliver a female and my daughter-in-law a male!

This is more or less what is happening today too. I will offer you 10 big candles and insert a fifty rupee note through the narrow slit in your collection box. In turn you should ensure that my son gets a US visa and I receive the first prize of the Kerala State lottery. The faithful are actually denigrating the saint to the level of a corrupt municipal clerk. The only difference is that the municipal clerk who takes your money as a bribe would do your work. But with the saints, you are not so sure. Finally, when the believer discovers that he lost his money and received nothing in return, he would not blame the dead man on whom sainthood was thrust upon by the church. The faithful would blame the failure only to his own lack of faith. So the next time he would try increasing the number of candles and the currency notes. And may crawl on his knees around the effigy of the saint a dozen time as added incentive to trigger the boon, Like a man, who never had the good luck to receive a single rupee in return for the money invested in lottery tickets, but continues to invest his hard earned money on more lottery tickets, the faithful continue with their silly gamble. If he or she eventually gets anything out of this exercise, there will be a celebration, propaganda and an advertisement in the newspaper ‘for favours received’. But, it has more to do with the laws of statistics than to any miracle. But the news hooks more people into this vicious cycle.

(Adapted from my book, ‘The Kingdom, The Power, The Glory’: The Story of Christianity from Christ to the Current Times for 21st Century Readers)

good.

Thanks.

I regret the delay in responding.

Regards,

Georgekutty